Calculation and Analysis

In Keith Burgun’s article Minimize calculation (in games worth playing) he distinguishes between two ways that a player can make decisions in a game: Calculation, and Analysis.

Calculation refers to a process of systematically searching for the ideal move by predicting future gamestates. For example, when you consider a move in chess, you know exactly what the gamestate will look like when you make that move, and you can predict what moves your opponent will be able to make, and that knowledge influences your decision. In a game like chess it’s very common to spend a lot of time going through though processes like “Let’s see, if I move my rook two tiles forward… he’ll be able to attack it with his bishop. If I move it three tiles forward… he’ll be able to attack it with his knight… but if he does he’ll risk getting it capture by my pawn. If I move it four tiles forward…”

Analysis is the method of making a decision that doesn’t involve calculation. In analysis, you don’t do any computation to systematically find a good move, the way you make decisions is driven by intuition.

Keith says that analysis is the preferable way of playing games, and I strongly agree. Fun in games (or at least, in strategy games or Abstract Ruleset Games. See my previous post for more detail) comes from learning about the strategic consequences of the decisions you make in a game. This learning process can only take place when you aren’t certain about if the move you make is the correct one.

The problem with calculation is that you can be certain about which move is the best, and that calculation is unecessary mental work. Decisions are only interesting in games when the player learns from them, and that can only happen when the player doesn’t know if the decision they make is the correct one – otherwise, why are they making the decision in the first place? Whenever you know which of your possible moves is best, the game has failed you.

Given that the core purpose of a game is to provide the player with interesting decisions that the player isn’t certain about, every moment spent calculating is at best moment wasted, and at worst a mental burden that distracts from the important parts of the game. Thus, games should seek to have as little calculation as possible. Keith’s article makes the same claim, but doesn’t go into much detail on exactly HOW to minimize calculation. I think the most important concept when one wants to minimize calculation is the concept of Information Generalizability.

Information Generalizability

Information generalizability is the measure of how useful the information that the player learns in one situation is in another, similar situation. If a game has high information generalizability, a strategy that works well in one situation will work similarly well in a similar situation. To have high information generalizability, a game needs to follow two principles:

1: The information that the player learns in a situation should be generalizable to similar situations.

2: It should be easy to identify which situations are similar.

The reason this property is important is that it is what allows analysis to be useful. If every small change in gamestate leads to very large strategic consequences, then the player can’t develop general knowledge about the game, they can only learn about very particular situations. In a game with no information generalizability, the information you learn in any given situation is completely useless to every other situation in the game, and there is no place for analysis, there is only calculation. In such a game, it is impossible to develop a heuristic mental model of the game, you must think about every single situation you encounter as being completely unique. There isn’t any meaningful learning going on, since there is nothing to learn from a given situation except for how to handle that exact situation.

A game with absolutely no information generalizability may not be possible, but there are plenty of games with very little. For example, chess has very little information generalizability. Imagine considering your next move in the middle of a chess game. The pieces are in a complex arrangement, and the positioning of each piece has large implications on the possible moves of many other pieces. You’d think about each move you could make, and how that would affect the moves your opponent could make. You would develop a complex web of risks and rewards and potential future gamestates. Now, imagine that your queen is moved one tile to the left. Much of the contemplation that you just did is useless. A seemingly tiny change in the state of the game has massive consequences, and thus the information that you learned in the situation before your queen was moved isn’t very generalizable to the situation after the queen is moved. The result of this is that chess is a very calculation-heavy game, since small changes in game state are too large for heuristic models to be very useful.

Here’s a concrete example of the difference in information generalizability in two different rulesets:

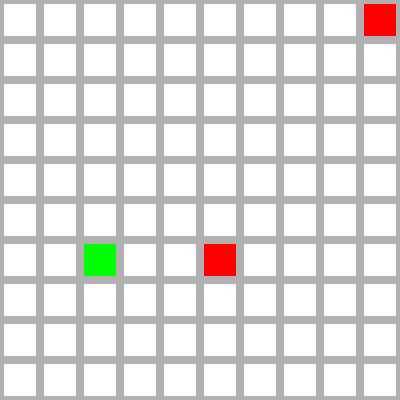

Here, the player is the green square, and the red squares are enemies. Each living enemy deals 1 damage to the player each turn, and the player’s goal is to kill all the enemies while taking as little damage as possible. The player can attack one enemy each turn, and every enemy has 1 health. The difference between the rulesets is in how the player’s damage is calculated:

Ruleset A: The damage the player deals each is the inverse of the distance between the player and the enemy.

Ruleset B: The damage the player deals is (5 – d % 4) / 10, where d is the taxicab distance between the player and the enemy. In other words, if d is divisible by 4 the player will deal 0.5 damage, if the remainder when d is divided by 4 is 1 the player will deal 0.4 damage, etc.

If you have any intuition about game design Ruleset B will seem ridiculous, but that intuition isn’t useful to developing a formal theory of design. The point here is to justify why that intuition is correct.

Under ruleset A, the ideal strategy is to attack the closest enemy first until it is dead, and then the farther enemy. Under ruleset B, however, the ideal strategy is to attack the farthest enemy first. (because the taxicab distance is 3 for the closer enemy and 13 for the farther, so an attack will deal 0.2 or 0.4, respectively)

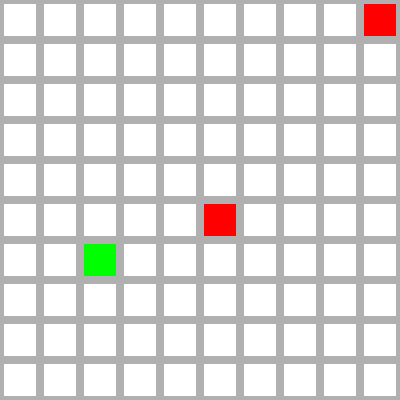

Now, consider a slightly different situation:

The ideal strategy under ruleset A is still the same, but for ruleset B it has changed: You should now attack the closest enemy first, then the second. (since the new taxicab distance for the closer enemy is 4 and thus the damage dealt will be 0.5)

This demonstrates that ruleset A has higher generalizability than ruleset B, since in A the same strategy was useful in the two similar situations, while in B a tiny difference in gamestate caused a large change in strategy.

The practical implication of this difference is that ruleset A involves much less calculation. Under ruleset A you can always easily come up with the best strategy just by briefly looking at the board. You simply attack the closest enemy first. Under ruleset B, however, you have to go through a significant amount of computation to find the ideal strategy.

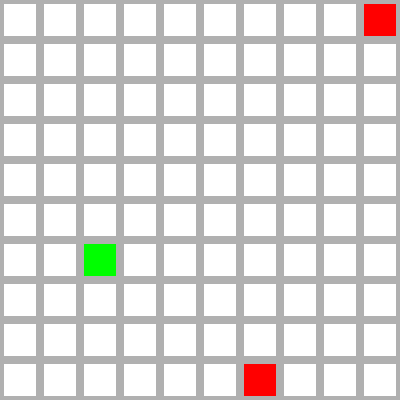

This example also demonstrates the importance of the second principle I mentioned earlier (“It should be easy to identify which situations are similar”) because there technically are situations that one could say are “similar” to the first situation, though the problem is that they aren’t easy to identify. For example:

This is strategically similar identical to the first situation, because the distance to the closer enemy is now 7, which leads to the same damage value as the distance of 3 in the first situation. However, it isn’t too easy to tell that the situations are similar at a glance, so the generalizability is still low.

Conclusion

So far I’ve spoken only about the positive consequences of high generalizability, but increasing the amount of information generalizability in a game isn’t always a good thing. Just as a game with no generalizability is undesirable because it would be purely calculation, a game with the maximum possible generalizability is equally undesirable because the same strategy would be ideal in every situation. In fact, increasing information generalizability might often correlate with a decrease in strategic variety and depth. A good game shouldn’t attempt to maximize generalizability over all else, but should be sure to take it into account. An ideal game will have enough generalizability such that analysis is a consistently viable, but not so much that it becomes strategically boring.

In my opinion, many abstract strategy games, such as chess, Auro, and Hoplite have this problem, and it is one of the biggest things holding them back. However there are also existing strategy games that manage to have a good amount of generalizability while also maintaining strategic depth, like XCom or Invisible Inc.

While information generalizability makes analysis useful, it doesn’t prevent calculation, or make it less useful. High generalizability increases the usefulness of analysis, but doesn’t decrease the usefulness of calculation. Calculation is something that can be applied to any ruleset, regardless of its generalizability. In order to make sure that the player is using analysis instead of calculation, you need something else, which will be the topic of my next post.