Introduction

The strategic thinking that happens in strategy games can be thought of as a process of forming plans. The player takes in information, and then forms a plan based on that information and their understanding of the game. When a player’s plan is interrupted, they are forced to adapt, and the process of adapting can also be thought of as forming a new plan. The process of forming plans and then learning which types of plans are better or worse at accomplishing the goal of the game is what makes games fun. Thus, it is important to understand how the structure of a game affects the player’s plans.

The main thing that causes players to change their plans is information that had previously been hidden becoming available to the player. When new information is introduced, plans that the player formed previously become outdated, and the player has to adapt their plan, or come up with a completely new one. Different games introduce information at different rates and in different patterns, and I call this property the game’s “information flow”. Different information flow patterns have different effects on how players can form plans, and I think that it is important for strategy game designers to actively consider information flow in their games, and how this flow influences the way players make plans.

Impact, and high-level and low-level plans

Not all information affects the flow equally, because the degree to which new information disrupts the player’s plans is not the same for all types of information. Some information has higher impact than other information. For instance, information about the location of the next enemy pod in XCOM is higher impact than the information about whether a particular shot hits or misses. The information flow is defined by the sum of the impact of all the information being introduced in each moment

Generally, low-impact information affects low-level plans, while high-impact information affects high-level plans. High level plans are those that are general and abstract, while low-level plans are more specific and concrete. High-level plans can be thought of as being composed of lower-level plans. If you have a high-level plan of “I will get rid of these monsters”, you could accomplish that by several different low-level plans like “I will approach the monsters”, “I will cast a weakening spell on the monsters”, and “I will attack the monsters”, and each of these low-level plans could change or be replaced with something else without getting rid of the overarching, high-level plan of “getting rid of these monsters”.

The speed of flow

In a game with too fast a flow, it will be impossible for the player to form a long-term plan. Any long-term plan that the player forms will quickly be disrupted by the new information, and will end up being useless. The player will simply stop forming long-term plans, and handle the game on a purely turn-by-turn basis. In other words, the game will be purely tactical, with no potential for any long-term strategic planning (except, perhaps, on a very general and abstract level).

In a game with too slow of a flow the player’s plans won’t be disrupted enough, meaning the player can form plans that reach to far into the future. To demonstrate this, we can consider a game with the no information flow at all. In other words, a single-player game with perfect information. This would be something like a single-player chess game with a very simple, deterministic enemy AI (real chess doesn’t count here, since the future moves of the other player are hidden information) The enemy AI needs to be simple, because if it’s too complex the player won’t be able to consider it very effectively, and effects caused by information the player hasn’t considered are effectively equivalent to new information. This type of game would be what Keith Burgun calls a “lookahead contest”, where the player can endlessly calculate into the future, and thus form plans for the entire game from the very start. In a game like this, all planning can be done at the very start of the game, and thus the process of actually “playing” the game isn’t very fun; it’s simply following the plan that you came up with at the start. Since there’s no new information coming in, your plan never gets disrupted, and so there’s never any reason to do any new planning.

A game with a slow, but non-zero information flow will suffer from many of the same problems, but to a lesser degree: there won’t be enough new information interrupting the player’s plans, and much of the gameplay will consist of simply following out plans, instead of coming up with them (the fun part).

Spiky Flow

There are countless conceivable shapes an information flow could take, so of course I can’t describe or comment on all of them here. However, there is one type of flow that I think is worth focusing on, what I call a “spiky” information flow.

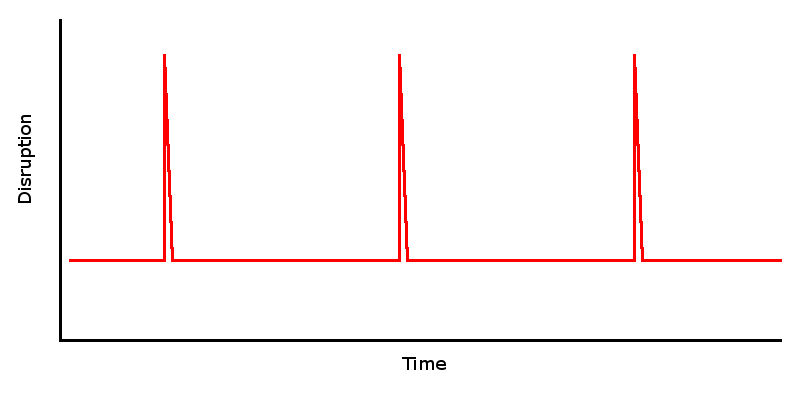

To wrap our heads around variable information flow, it helps to render it as a graph, plotting disruption against time. This graph represents a spiky information flow:

A good example of a game with roughly this type of flow is the 2012 remake of XCOM, and it’s sequel XCOM 2. This type of flow is characterized by having a slow flow most the time, but with occasional spikes, where a lot of high-impact information is introduced. In XCOM, these spikes would be the discovery of new enemy pods. In general, spikes have impact large enough to disrupt the almost all low-level plans, and cause the creation of new plans. High-level plans can potentially survive past the spikes, but the low-level plans are restricted to the periods of time between spikes, not across them. In XCOM, whenever you discover a new enemy pod, your vague, high-level plans like trying to get to a certain point on the map, or trying prevent a particular unit from taking any damage, can stay the same. Your low-level plans, like where you’re going to move your units or what to shoot at next, are completely interrupted, since you have so much new information to deal with.

The flow in between the spikes, which I’ll call the “idle” flow, is there to make sure the player still has to adapt somewhat in between the spikes, but is slow enough to allow mid-level plans to last for a while. In XCOM, the idle flow comes mostly from the results of shots and from enemy movements. The hidden information involved in these mechanics ensures that the gameplay between the activation of pods still requires adaptation. If XCOM had no idle flow, and was deterministic other than the location of enemy pods, the player would be able to form a plan for dealing with each enemy pod right after it activated, and the process of actually carrying out the plan would be boring, since it wouldn’t require any adaptation.

The idle flow can be slower than what might normally be ideal if the game had a constant flow, because the upcoming spikes prevent the player from forming a plan that goes too far into the future. However, it’s still important to make sure the idle flow isn’t too slow, or each idle period will be almost like it’s own perfect information game, with all the problems associated with that: play will consist mostly of following out plans formed right after each spike, with little new plan-formation happening between spikes.

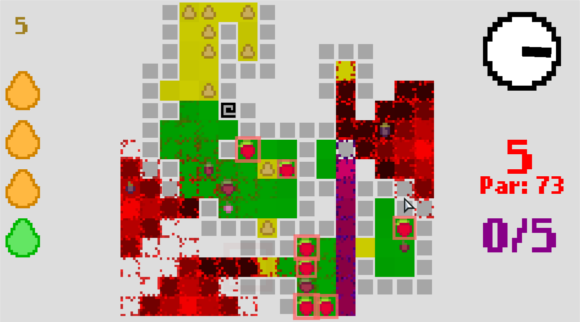

Another example of a game that uses a spiky flow is my own game, Brazen Berry Bonanza (which will be released very soon! You can try out the latest prerelease version here).

In Brazen Berry Bonanza, you try to grow certain plants while preventing other, evil plants from growing. One of the early design decisions I faced was how to spawn evil plants. The first and most obvious solution was just to have a single evil plant spawn every once in awhile, at a regular interval. In trying this, I found that the game had the problems that I described as the problems of a game with too fast a flow: it was impossible to form a plan past the immediate future.

I then tried an alternative: instead of spawning one new evil plant at a time, evil plants would spawn several at a time in “waves”, with the time between waves being longer than it had been in the one-by-one spawning. The result was immediately and drastically better. Intuitively it seemed to make sense that this was better, but I didn’t have a good theoretical explanation as to why it was better, and it was that situation that lead me to come up with the ideas I’m describing in this article.

In general, I think there are two big advantages to using a spiky information flow:

If a game has too fast of an information flow, changing to a spiky flow can slow down the information flow for the majority of the game by gathering much of the high impact information into the same area. Imagine a version of XCOM without a spiky flow, one in information was introduced more consistently. Instead of the enemies being introduced in large chunks every few turns, one or two enemies would be introduced each turn. This version would be less fun than real XCOM, largely because the information flow would be too fast. It would be difficult to plan for anything past the current turn, since the new enemies would immediately disrupt any plan you made. By having the introduction of new enemies group into occasional chunks instead of being evenly distributed, the time between chunks becomes much easier to plan for.

It avoids the normal problems of a slow flow game by putting a hard limit on how far low-level plans can reach. Normally a game with a slow flow allows the player to form low-level plans too far into the future, but in a spiky flow the player knows there is going to be a huge event coming up that will disrupt all of those plans. Games with too slow of information flows could perhaps be improved using this pattern by introducing occasional spikes to prevent planning that goes too far.

Consistency

One important difference between XCOM and Brazen Berry Bonanza is that the positioning of the spikes, and the rate of the idle flow, is more consistent in BBB than in XCOM.

In XCOM, a new spike happens when the player activates a new pod. This means that the spikes in XCOM aren’t necessarily very consistently spaced, since it’s possible for the player to discover two pods in very quick succession, or go through a long period of not finding any pods at all. Comparatively, Brazen Berry Bonanza has a very consistent flow. The spikes are waves of new evil plants spawning, which happen on a perfectly consistent interval of around 1 minute. Additionally, there is always a clock displaying the time until the next wave.

The advantage of this consistency is that the player knows exactly when their plans will be disrupted by a spike, and thus won’t ever have a long-term plan unexpectedly interrupted. Just as a flow that is too fast discourages players from planning too far into the future because of constant disruption, the constant threat of a spike can do the same, to a lesser extent. If the player knows exactly when the next spike will happen, like they do in Brazen Berry Bonanza, they’ll be able to confidently plan up until the spike without fear of an unexpected interruption.

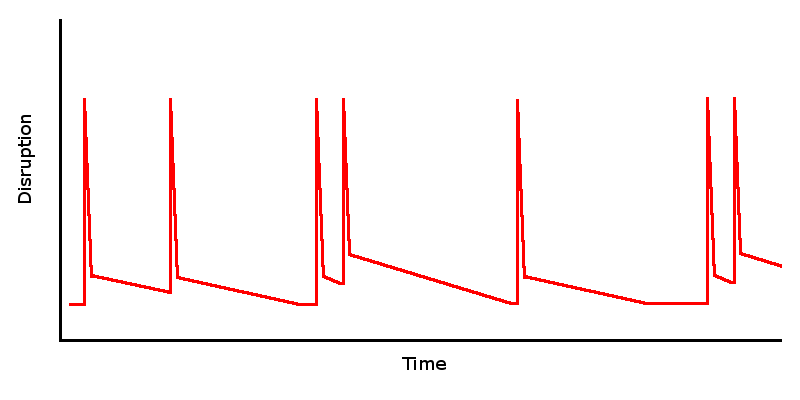

Games don’t always need to have perfectly consistent spike-schedules, but I do think that XCOM allows for too much inconsistency. XCOM 2 improved on XCOM2012 in this regard, by having spikes come not only when the player discovers a new pod, but also when a group of reinforcements is called in, which is telegraphed several turns in advance.

The idle flow in XCOM is also inconsistent. It comes mostly from the results of shots and enemy movements, both of which are contingent on the existence of enemies. When there are more enemies, there will be a faster flow, and when there are fewer enemies, there will be a slower flow. This means that the idle flow tends to be at its highest right after a pod is discovered, and decreases as the enemies are killed. If the player discovers two pods in quick succession, the idle flow will be nearly double what it normally is after discovering a single pod.

In Brazen Berry Bonanza, the idle flow comes from the way plants grow, where seeds and berries spawn, and what new types of seeds the player gets, all of which tend to happen very regularly. This means that the idle flow has roughly the same rate at any point, and additionally it means that I, as a designer, have a lot more control in fine-tuning the idle flow than is possible in XCOM.

Brazen Berry Bonanza’s flow diagram would look almost identical to the previous image showing what a general spiky flow looks like, but XCOM would look somewhat different. With the possibility for inconsistency in both the spike-schedule and the idle flow, the real flow diagram of a match of XCOM might look something like this:

Conclusion

The essential thing that makes strategy games fun is the process of forming plans, and the information flow has a huge impact on how the player forms plans. It’s important to make sure the flow as a whole isn’t too fast or too slow, but for a more nuanced view you need to look at the way the flow changes over time. A good pattern to follow is the spiky information flow, in which high-impact information is collected into discrete spikes that happen at regular intervals, with a slow, regular flow of information between the spikes. Carefully considering the way information is introduced, and how that impacts the player’s ability to form plans, is essential to designing a good strategy game.

Thanks to evizaer for helping me edit this article.